recursion() { recursion(); }

You have used recursion. Wanna know what your programming language does under the hood to support it?

Any programmer can’t imagine life without recursion. Although every recurisive algorithm can be written in an iterative manner, there’s a certain beauty to writing recurive code. Easy to use & grasp. However, programming languages haven’t always supported recursion. Algol 60 was the first language to support it, mostly due to the genius of Djikstra. I read in a couple of places that Lisp was the first one to implement it. Both Lisp and Algol 60 were developed & released around the same time, so I guess no one really knows.

This blogpost turned out to be much longer than I anticipated, so you might want to read it in parts. So before I jump into the nitty-gritty of recursion, here’s some things you need to know.

The Stack & Heap

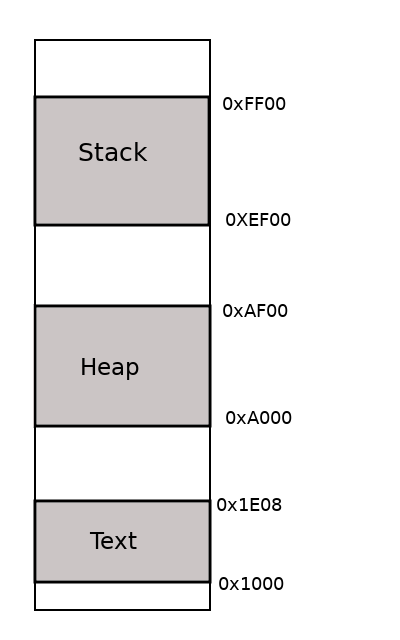

A process is an instance of a running program. For operating systems, the process is the ‘thing’ the OS allocates resources to. Every process has a couple of segments loaded in memory when it runs. The most important ones for today’s story are the Heap and the Stack. The heap is the data structure where the running program stores the global variables, or the variable allocated memory using malloc() in C, or the new keyword in C++ & Java. The lifetime of the variable is till it gets deallocated or the program ends. The stack is where the local variables are stored. They remain valid till the function is being executed. In most of the languages, the function that is being executed(callee) cannot access the variables of the function that called it (caller).

Stack operations ?

Think of the stack as a pile of books. You can only access what’s at the top. Pretty easy, huh. The stack has two operations, push and pop. the push operation is like putting a new book on the top of the book stack. The pop operation is like taking away the book at the top. Now that you know the basic terminology, the next part should be easy.

The stack and heap in the process image

|

|---|

| How the process looks in memory. The image is not drawn to scale. The hex numbers on the right are the addresses in memory. |

| NOTE: Its not necessary that all programs have the exact same addresses as the example program |

Every process has some memory allocated to it. Memory is space on the RAM. The memory that each process gets, is numbered from 0x0000 to whatever the limit is (which I assume as 0xffff for my examples below). In reality, the limit depends on things like processor bit width, virtual memory space (and possibly more things which I may not know at the moment). I’m just focusing on the text, heap and stack sections. The text section is at the lower addresses. It stores the assembly code that should be executed. The heap starts after the text section. As you allocate memory during runtime, the heap grows upwards. The stack begins at the highest memory address, and grows downwards. This is a bit counter-intuitive, so read this carefully.

The top of the stack is denoted by the $sp register. Think of a register as a variable name in assembly programs. Registers are usually written with a $ sign as a prefix. Also, sp is an abbreviation for stack pointer. The $sp register points to the top of the stack, where the last element was pushed. Again, understand, the $sp stores the address of the top of the stack, not the data itself. This means that all the data stored in memory locations 0xffff to the value in the $sp register is the data on the stack. If the $sp value is 0xff00, the last element was pushed in the memory location 0xff00. The stack contains 255 (=0xffff-0xff00) bytes of data in it.

A small but necessary detour: most architectures (actually memory) now (and have been since a while) are byte addressible. This means that each memory location stores one byte. So when I say that the memory in my example goes from 0x0000 to 0xffff, it is 16^5 * 1 byte, aka 1 MB.

Suppose we want to push 1 byte of data on the stack. In such a case, the stack has to grow. Since the memory is byte addressible, we need one memory location to store the value. Thus, the stack pointer register is updated $sp = $sp - 1. Don’t get confused here. The stack is growing (in terms of the book example, the pile is growing taller). Remember that the stack here grows downwards. So if you push 4 bytes on the stack, the $sp register is updated as $sp = $sp - 4. If you want to pop 2 bytes from the stack, you update it as $sp = $sp + 2. Apart from making it confusing for you to understand, an interesting consequence of this is the buffer overflow attack, which I probably will cover in a future article.

Recursion

Now that you’ve understood this, let’s move on to recursion.

The reason some languages support recursion, while others do not, is due to the way they store something called the activation record in memory at runtime.

Now what’s the Activation Record?

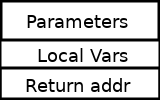

Every function that you write has an associated activation record. Think of it as a place to store the local variables, function arguments, the return address and other stuff that the function needs. You can visualize it like this

|

|---|

| The activation record |

Now, the size of the activation record depends on the number of parameters, the number of local variables and the size of the return address.

If this concept feels too abstract for you, consider this analogy. Imagine you are solving problems from a book. There are three books, A, B, C. While solving problems, you need to do some rough calculations, take some notes about the stuff you’re reading. Suppose you are reading book A, you have a set of calculations and notes for the page you are reading. Now if you need to solve some question from book B to fully understand concepts, you will have to take a new paper sheet to write the calculations for the new problem. However, to ensure that you do not forget where you return to once finished, you write the page number from book A that you were working on. You can think of the ‘paper sheet’ as the analogy for the activation record.

First, lets move onto why recursion was not supported in really old languages.

The real reason recursion wasn’t supported

Continuing with the earlier analogy of the books, old compilers would make executables with exactly one ‘paper sheet’ for each book. If you were reading book A, which required you to solve something from another part of the same book. You’d be forced to use the same paper sheet. You’d be overwriting the old notes/calculations and especially the name and page number of the book which forced you to read book A! Repeating the same thing in formal terms now.

So, in recursion-less languages, activation records were made when the program was being loaded into memory. This means the number of activation records in memory could not be changed at runtime. There would be exactly 1 activation record for each function. To summarize in Computer Science terminology, the activation records were statically stored.

So the caller would know the exact address where all the activation record entries would be stored and could write there. The function, which was called could read from there. Imagine the case, where a function tried to call itself. Since there is only one activation record, it would overwrite all the values in the activation record. We just lost the state of the program, and the address the function should return to!

Also, recursion of the type, where one function calls another, which calls the caller wouldnt be supported. eg A()->B()->C()->A() would not be allowed.

So in a line, recursion wasn’t supported in some languages because they created activation records in a static manner.

But what about languages that support recursion?

Using the same analogy, new compilers created binaries that did not have any pre-created paper sheets for each book. Instead, everytime a new book had to be referred to, a new paper sheet was made, and the old one was kept on top of the pile of paper sheets till that point. Once you were done referring to a particular page, you could discard the paper you were working on. You have the last book and page number on your current page. You have the notes of that page on the top of the stack. What a great analogy!

One could guess that in these cases, activation records are stored dynamically. This means that they are created at runtime, and there is no (theoretical) limit on the number of activation records that can exist in memory. There are 2 areas where activation records could be stored at runtime, the stack and the heap.

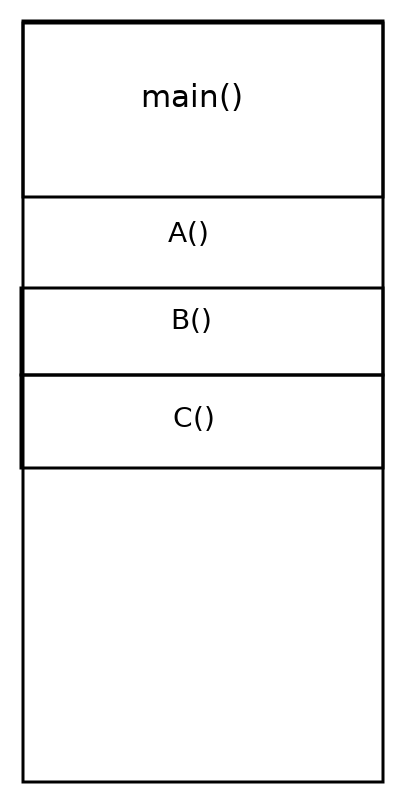

Storing them on the stack offers the benefit of maintaining the order in which the functions were called. Suppose the function chain called is A()->B()->C(), the control wont return to B till C returns, and the activation record of C is popped off the stack. In short, the stack is an absolutely perfect data structure for supporting function calling and recursion.

This is how it would look..

|

|---|

| How the stack looks when main()->A()->B()->C() |

Interstingly, I haven’t found anyone explaining why the heap is not used for storing activation records. If I were to use the heap to store the activation records, I would need a register to store the address of the first entry in the heap, which we could call the activation record pointer. We could use relative addressing to access those memory records, as we know the pointer and the offset. But then, the question of how to save the value of the activation record pointer arises, and then we need a stack. Allocating memory on the heap is computationally intensive, and since we’ll need a stack even in this case, it is just better to use the stack for storing the activation records. My 2 cents on probably why the people who decided to directly use the stack, and not heap+stack did so.

Again, to summarize, the reason why recursion is supported is that the activation records are created & destroyed in a dynamic manner. I feel that the confusing part for you must’ve been the stack growing from top to bottom in memory. This design choice has some curious effects, one of which is buffer overflow attacks and return oriented programming attacks.

This is one of the first technical blogs that I’ve written. If you feel that I can improve in anyway, drop a comment below. I’ll love to have your feedback!